Mayor Tom L. Johnson was called (by journalist Lincoln Steffens) the best Mayor of the best-governed city in the United States.

Tom L. Johnson moved to Cleveland in 1883 and soon afterwards bought a mansion on the ‘Millionaire’s Row’ of Euclid Avenue. He converted from a conventional business tycoon to a radical reformer after reading Henry George’s Social Problems, in which the political philosopher expounded his belief that poverty and misery were a result of society’s newly created wealth becoming locked up in increasing land values, and advocating a Single Tax on land in place of wastefully taxing the productive activity of capital and labor.

He also witnessed the terrible Johnstown Flood of 1889 which left him with a deep resentment of what he called ‘Privilege’. The disaster had been caused by the improper maintenance of a dam holding a private recreational lake, owned by Henry Clay Frick and other Pittsburgh industrialists, who escaped all responsibility for it. To Johnson, the flood exemplified the inadequacy of charity and weak ‘remedial measures’ to solve society’s problems.

The issue of privilege gradually made Johnson reconsider his own business career. ‘Traction’ (streetcar) companies depended on route franchises granted by city councils; political connections and payoffs gave favored companies the upper hand. In an era when most everyone rode the cars, the stakes were high, and battles for franchises were often the hidden issue behind cities’ factional strife.

The issue of privilege gradually made Johnson reconsider his own business career. ‘Traction’ (streetcar) companies depended on route franchises granted by city councils; political connections and payoffs gave favored companies the upper hand. In an era when most everyone rode the cars, the stakes were high, and battles for franchises were often the hidden issue behind cities’ factional strife.

Johnson always pointed out that he could speak with authority, because he was a streetcar baron himself. In Cleveland, he came into conflict early with Mark Hanna, the powerful local businessman who by 1894 would be the leading power broker of the Republican Party, the man credited with putting fellow Ohioan William McKinley in the White House.

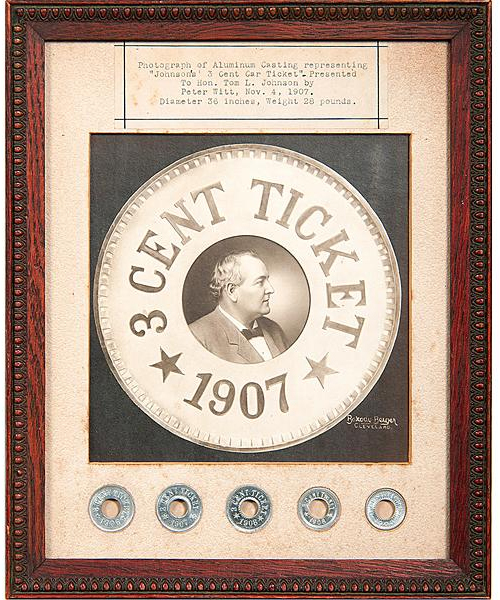

When companies with a monopoly of transport on a route were able to charge five cents for a ride, he made the ‘three-cent fare’ a cornerstone of his populist philosophy.

In 1901 he decided to run for mayor of Cleveland and his campaign electrified the city. Johnson liked to rent large circus tents and set them up on neighborhood lots, attracting big crowds for whom he would deliver a powerful speech, banter cheerfully with hecklers, and finish with a stereopticon show with a political moral. On April 1, 1901, he was elected with 54% of the vote.

One of the campaign issues had been a valuable piece of city-owned downtown lakefront property, which outgoing mayor John H. Farley and council had agreed to hand over to the railroads without compensation. Johnson obtained a court injunction to stop the giveaway and saved the land for the city. Today this land is home to Cleveland Browns Stadium, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the Great Lakes Science Center.

Mayor Tom L. Johnson’s four terms in office transformed Cleveland. He paved hundreds of miles of streets and expanded the city’s park system, building a large number of playgrounds, ball fields and other facilities. To popular acclaim, the mayor tore up all the ‘Keep off the Grass‘ signs in the city parks, a symbol of his belief in changing parklands’ role from passive to active recreation.

Johnson eliminated the rubbish haulers’ franchises and replaced them with a municipal department and he hired back all the men who had lost their jobs. Public bathhouses were built in the poorest neighborhoods. Johnson also began work on the monumental West Side Market, one of Cleveland’s best-known landmarks.

He established the country’s first comprehensive modern building code in 1904; the code became a model for many U.S. cities.

The physical symbol of Johnson’s revolution in government is Cleveland’s civic center, a spacious park surrounded by public buildings, called simply ‘The Mall’.

He founded the Municipal Light and Power Company, and though political opposition kept him from expanding it, the next Progressive mayor, Newton D. Baker, built a new plant that opened in 1914 as the biggest public utility in the U.S.

Johnson’s policies made him an extremely divisive figure. He depended heavily on the vote from ethnic neighborhoods on the West Side, where his three-cent fare streetcars operated. In the middle and upper-class sections of the East Side, opponents railed against policies they called expensive and ‘socialistic’.

The revolution in government Johnson effected in Cleveland made him a national figure. Melvin G. Holli, in The American Mayor: The Best and the Worst Big-City Leaders polled American historians and social scientists to find the best city mayors throughout U.S. history. They placed Johnson second on the list, behind only Fiorello La Guardia of New York City.

His statue was erected on Public Square (NW corner) in 1915. He is holding Henry George’s famous book, Progress and Poverty.

There is also a statue of Mayor Tom L. Johnson outside the Western Reserve Historical Society.